Chasing Centuries: top agave book of 2018

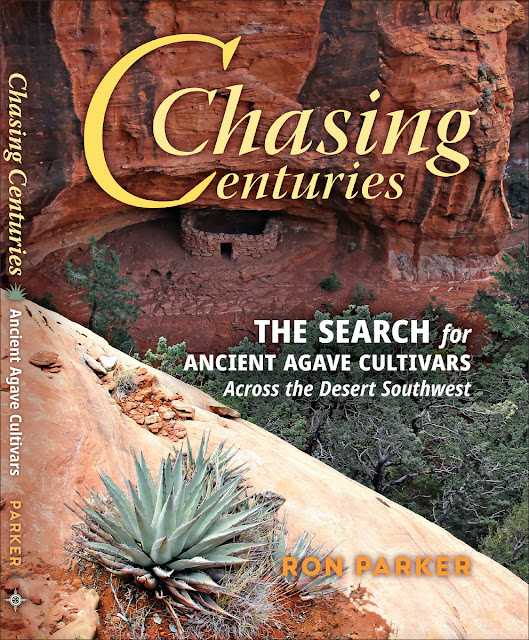

Considering how few books there are about agaves (I reviewed four in this post), any new volume about my favorite plant group is a reason for celebration. Even better when it's a truly original book—one that goes where no other book has gone before. Chasing Centuries: The Search for Ancient Agave Cultivars Across the Desert Southwest (Sunbelt Publications, January 2019) by Ron Parker does just that.

A few years ago, Ron and Greg Starr took me on a hike in the Waterman Mountains northwest of Tucson to see Agave deserti var. simplex growing in habitat. Ron talked at length about his travels all over Arizona to document endemic agave populations, especially domesticated agaves—cultivated by pre-Columbian cultures for food and myriad other uses. I could tell this wasn't just a casual interest for Ron. It was a passion. Ron was driven, the way all explorers are, to go further, look harder, dig deeper. You might call it an obsession, but it's the good kind that fills you with a curiosity you simply can't let go. Chasing Centuries is the culmination of Ron's agave hunts. And it's glorious.

Ron Parker, the book's author page states, "is an outdoorsman, xeric plant enthusiast, and amateur botanist who spends half his time gardening and the other half exploring natural habitat across Arizona and neighboring states."

Amateur comes from the Latin amare, meaning to love. That's the perfect word to describe Ron's pursuits. He does what he does not because he has to, but because he loves to. That also shows in Ron's other main endeavor, Agaveville.org, the hangout for agave lovers and other xeric plant enthusiasts on the Internet. I'm not as active on Agaveville as I'd like to be (you know, work—that great monopolizer of time), but whenever I need an answer, that's where I go.

Chasing Centuries is divided into four parts: "The Historical Perspective," "Agaves of the Region," "Notes from the Field," and "Addenda."

Ron introduces us to the three main cultures in what is now Arizona who cultivated agaves near their settlements, sometimes on a surprisingly large scale: the Sinagua, the Salado and the Hohokam. Based on archaeological evidence, we know that they employed a variety of farming techniques. This included terracing to maximize the land available for agriculture, and building dams to optimize the use of water and control erosion. In the early 1980s, evidence of an ancient Hohokam rock mulch farm was found north of Tucson; the authors of the resulting study suggest that the 1,200 acre area they examined might have been home to more than 100,000 agaves, producing an annual harvest of 10,000 agaves, or "forty metric tons of edible product."

The agaves occurring naturally in Arizona include A. ×ajoensis, A. ×arizonica, A. chrysantha, A. deserti var. simplex, A. mckelveyana, A. palmeri, A. parryi var. couesii, A. parryi var. huachucensis, A. parryi var. parryi, A. parviflora, A. schottii, A. schottii var. treleasei, A. toumeyana var. bella, A. toumeyana var. toumeyana, A. utahensis var. utahensis, and A. utahensis subsp. kaibabensis. Ron gives an overview of each taxon; a map shows where it's found. As an example, here's the page spread for Agave chrysantha:

Considering how long these agave cultigens have survived, it's particularly sad to see them declining in their native habitats, some even pushed to the brink of extinction. The reasons are not hard to understand: 30+ years of drought conditions, a marked increase in the number and scope of wildfires (especially hard to overcome for species that don't produce viable seeds), and the inevitable construction and development that engulfs ever larger tracts of what once was wilderness. To make matters worse, agave mite infestations have climbed to alarming levels in recent years, weakening vulnerable populations even further. "The future is not bright, boys and girls," Ron laments. "We’ll need to enjoy these wonderful agaves while we can."

A few years ago, Ron and Greg Starr took me on a hike in the Waterman Mountains northwest of Tucson to see Agave deserti var. simplex growing in habitat. Ron talked at length about his travels all over Arizona to document endemic agave populations, especially domesticated agaves—cultivated by pre-Columbian cultures for food and myriad other uses. I could tell this wasn't just a casual interest for Ron. It was a passion. Ron was driven, the way all explorers are, to go further, look harder, dig deeper. You might call it an obsession, but it's the good kind that fills you with a curiosity you simply can't let go. Chasing Centuries is the culmination of Ron's agave hunts. And it's glorious.

Ron Parker, the book's author page states, "is an outdoorsman, xeric plant enthusiast, and amateur botanist who spends half his time gardening and the other half exploring natural habitat across Arizona and neighboring states."

Amateur comes from the Latin amare, meaning to love. That's the perfect word to describe Ron's pursuits. He does what he does not because he has to, but because he loves to. That also shows in Ron's other main endeavor, Agaveville.org, the hangout for agave lovers and other xeric plant enthusiasts on the Internet. I'm not as active on Agaveville as I'd like to be (you know, work—that great monopolizer of time), but whenever I need an answer, that's where I go.

When agaves are getting ready to flower, Ron explains, "leaves thin, marginal spines wane, and the base begins to swell as sugars are collected for the production of nectar." This is the time for harvesting:

Leaves are trimmed off, and agave cabezas (Spanish for “heads”), now looking for all the world like giant pineapples, are collected and tossed into a makeshift oven for cooking and processing. A pit is dug, and a coal fire started at the bottom. Once a fire is raging, cabezas are added, then covered, and another fire started on top. Two to four days later, roasted agave cabezas are collected and eagerly consumed. Roasted flesh is soft and sweet, often compared to molasses and sweet potatoes. In addition to consuming product as it came from earthen ovens, a considerable portion might have been worked into cakes, which were thoroughly dried and stored for winter consumption or trade. Flowers and unopened buds could also be processed as food items.

But the use of agaves went well beyond food: Leaves became fiber for rope and textiles, terminal spines served as needles and nails for crafting and construction, and soap was extracted from the roots.

Surviving petroglyphs are vivid proof of how important agaves were to Arizona's pre-Columbian cultures:

This is a good time to mention the photos in the book, most of them taken by Ron. Contrary to the idiom, pictures aren't always worth a thousand words, but in this book they are. I'm not only talking about photos of agaves, but also of the places where they grow and where their domesticators lived—the environmental context. Take a look at what's left of this Salado cliff dwelling high above Roosevelt Lake: what an evocative setting even though this man-made reservoir didn't exist then. Even today there are several large stands of Agave delamateri nearby.

The heart of Chasing Centuries is Part II, "Agaves of the Region." On 80 pages, Ron describes all the agaves native to Arizona, including both naturally occurring species and what Ron calls "pre-Columbian cultigens."

Cultigen is a key term in this book, and an important concept to understand. This how Ron defines it:

Any plant that is deliberately selected for or altered in cultivation. Cultigens can have names at any of many taxonomic ranks, including those of species, variety, form, and cultivar. The words cultigen and cultivar may be confused with each other. All cultivars are cultigens, because they originate in cultivation, but not all cultigens are cultivars, because some have not been formally distinguished and denominated as cultivars. Though "cultivar" is used informally in our title, these agaves have been formally described as species, rather than cultivars, so are more properly referred to as cultigens.

In Chapter 6, Ron introduces Arizona's pre-Columbian agave cultigens: A. delamateri, A. murpheyi, A. phillipsiana, A. verdensis, and A. yavapaiensis. While these have species status today, there are indications they are man-made selections or hybrids:

In some instances, it seems native Americans found room for improvement in naturally occurring agaves. By employing techniques as familiar as selection and (presumably) hybridization, and possibly other techniques less familiar, ancient skilled horticulturalists forged a symbiotic relationship with agaves by developing and nurturing new cultigens to better suit their varied purpose. And this is where our Arizona pre-Columbian cultigens step in. In this case, the primary qualities selected and bred for appear to be fiber and food.

Most of our Arizona cultigens were likely planted some 700–1,100 years ago, and share certain qualities. And it is many of these very qualities that strongly suggest an anthropogenic rather than natural origin.

Desirable qualities include a manageable size (i.e. neither too small nor too large); large heads with increased sweetness (i.e. more to eat and a better taste); and pliable leaves that are easier to cut (i.e. more efficient harvesting). The most striking feature common to all five cultigens is the way they reproduce: they make large numbers of offsets but virtually no viable seeds.

Prolific pupping made the work of ancient plantsmen significantly easier. Starting plants from seed is a time-consuming process and fraught with failure; compared to that, separating and replanting offsets is child's play. How exactly these cultigens lost their ability to set seeds is a not entirely clear, but it may simply be a result of rigorous selection over centuries.

Ultimately, this reproductive behavior is the reason why these cultigens have maintained their own identity for so long. If they were fertile, they would have mixed with naturally occurring species, or, as Ron says, "gone feral, fomenting toward an indecipherable nucleotide stew."

|

| Map showing where the five cultigens are found |

Each cultigen, A. delamateri, A. murpheyi, A. phillipsiana, A. verdensis, and A. yavapaiensis, is described in detail, and photos show each species in habitat. You'll also see what the flowers look like—something most of us will probably never get to witness in real life.

|

| Agave delamateri |

|

| Agave verdensis |

Ron ends the book on a cautiously positive note—as positive as one can be, given the real threats to wild populations. The Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix has all five cultigens in their collection and is actively propagating them. Agave murpheyi is a popular landscape plant in the Phoenix area, and the other species may become more widely available through tissue culture.

The last paragraph in Chasing Centuries is so hauntingly beautiful that I want to quote it in its entirety:

Finally, to anyone visiting sunny Arizona, do yourself a favor and take a day to drive up into the mountains, where time stands still and tall, glorious agave stalks dot the landscape. There is something absolutely magical about gardens planted and nurtured by Gaia herself. And if you listen very closely, and there isn’t too much wind, you may hear the whispers of ghosts, still tending agave gardens originally planted centuries ago.

That's exactly what I plan to do on my next trip to Arizona. And I'll have my copy of Chasing Centuries with me for reference.

|

| Agave phillipsiana in red rock country |

Chasing Centuries won't be available in time for the holidays, but it would make a fantastic New Year's gift for folks interested in the three A's: agaves, archaeology, and Arizona.

Book text and images © 2019 by Ron Parker. Used with permission.

© Gerhard Bock, 2018. No part of the materials available through www.succulentsandmore.com may be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated or reduced to any electronic medium or machine-readable form, in whole or in part, without prior written consent of Gerhard Bock. Any other reproduction in any form without the permission of Gerhard Bock is prohibited. All materials contained on this site are protected by United States and international copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published or broadcast without the prior written permission of Gerhard Bock. If you are reading this post on a website other than www.succulentsandmore.com, please be advised that that site is using my content without my permission. Any unauthorized use will be reported.

What a unique perspective this book is, melding so many aspects of Agave cultivation. I hope to visit AZ in 2019, and because I lived there for a few years in the 70's and went there frequently for family vacations as a child I have a deep, almost spiritual connection to the place. I will definitely acquire this book before I go-and your last photo is from the place I lived.

ReplyDeleteAnother book to look forward to. My shelves are sagging due to your recommendations. All great by the way! Thanks. Best of the season Gerhard.

ReplyDeleteI'll definitely join up with whoever travels to Arizona to trace Ron's footsteps. Thanks for such a thorough review of what looks like a very worthy read!

ReplyDeleteA fascinating post and review -- and a book that seems it will become a classic quickly. The author's photos are exceptional, too. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThis book is a keeper. I don't get out among the rocks and sand now. The book helps keep my interests. When one of the many Agave I have blooms, I know exactly what reference to turn toward. It seems that Ron Parker has been able to follow an earthly passion.

ReplyDelete